The Roses of No Man's Land

WENCHES IN TRENCHES

®

JUST WHERE DO WE START WITH THIS MAGNIFICENT WOMAN?!

Hannah Mary Frances Ivens was born in 1870 in Little Harborough, near Rugby, Warwickshire. The youngest of five children to William, a Farmer and Timber Merchant, and Elizabeth (née Ashmole - descended from Elias Ashmole of Ashmolean Museum (Oxford University) fame. Her siblings were Edith, William, Ethel and John.

When she was just 10 years old, her mother died but it seems that young Frances was the apple of her father's eye. Together with her sister Ethel, Frances was educated at boarding school in Cheltenham, where she excelled in French, something which would serve her well in years to come. Her early years were comfortable and undemanding, playing tennis, riding and gardening. And then, one day her life changed when she met Margaret Joyce. A student at the London School of Medicine For Women, Joyce inspired Frances to pursue a career in medicine and in 1894, at the age of 24, having passed her London Matriculation, she entered the London School of Medicine For Women, doing her clinical studies at the Royal Free Hospital.

Frances qualified in 1900 with a gold medal in Obstetrics and Honours in Forensic Medicine. In 1902, she qualified MB BS (Bachelor of Medicine and Surgery) with first class honours. In 1903 she obtained the degree of Master of Surgery (MS), the most advanced qualification in surgery and only the third woman ever to achieve this. She obtained further postgraduate experience in obstetrics and gynaecology in Dublin and Vienna. Qualified women doctors, at this time, had few opportunities to secure house posts in major teaching hospitals.

Image courtesy of Lord Riddell; Dame Louisa Aldrich-Blake. The Wellcome Collection L0030958

Significantly, during her time there she made life-long friendships with Elizabeth Courtauld and Dr Augusta Berry (née Lewin), both of whom worked with her at Royaumont during the First World War.

In 1907 she left London for Liverpool and joined a new unit at the Stanley Hospital (originally known as the Hospital for the Treatment of Diseases of the Chest and Diseases of Women and Children) as Honorary Gynaecological Surgeon, becoming the first woman to hold such a post. The beds at this unit had been specially endowed on the condition that they should be in the care of a woman practitioner.

Frances was instrumental in building up a large gynaecological out-patient department and she was also appointed honorary surgeon to the Liverpool Samaritan Hospital. Her position and reputation allowed her to fight for causes she believed in and she became a great advocate for women, children and wider feminist causes. Frances became a leading member of the North of England Medical Women's Society, so much so that Dr Catherine Chisholm (1878-1952), the first woman to qualify as a doctor at the Manchester Medical School, described how Frances proved to be an inspirational leader. When Manchester and Liverpool medical women joined forces to form the North of England Medical Women’s Society, Dr Chisholm said of Frances; ‘her social experience was a valuable asset for she took part in everything going on in Liverpool’. Frances was also active in the suffrage movement and was chair of the Liverpool branch of the Conservative and Unionist Women's Suffrage Society.

In 1909, alarmed by the 14% incidence of gonorrhoea she recorded in her patients, Frances fought for more awareness of venereal disease affecting women. Raising the issue again in 1914, Frances bemoaned the fact that the medical profession concealed the truth from women to spare them mental worry in addition to physical illness. ‘It is unfair that a woman should be subjected to repeated infection without her consent and if unaware of the nature of the disease she was unlikely to submit to efficient treatment. If any change were to be made by the medical profession in this matter, it must be made by the profession as a whole.’

Perhaps it is possible to see and understand a little of of Frances’ personality from an inaugural address she gave in October 1914 to young medical students at the London School of Medicine for Women. In her speech, Frances outlined ‘Some of the essential attributes of an ideal practitioner’. The parallels with her own achievements before, during and after the war are striking and the following extracts embody many of her personal qualities of generosity, perseverance, diplomacy, leadership and fairness:

She (the ideal practitioner) would spare herself no effort to give physical and mental relief with as little pain as possible. She would gain the confidence of others... impressing them by a well-balanced judgement. Not always counting the cost to herself, she would be rewarded bountifully by the affection of her patients. Having a strict sense of duty, her word would be her bond, and what she promised she would perform faithfully, to the best of her ability. Not lacking in courage, she would be able to face difficult situations with calmness, and would not be dismayed by the first obstacle. Not forgetting that she was a woman as well as a doctor, she would use her intuition on many occasions with startling success. Tolerant of others she would express no harsh judgements. Honesty and sincerity would lead her to expect to find truth in others and she would be rarely disappointed.

Surgeon - Médecin Chef

The Scottish Women's Hospital at Royaumont, France (1914 - 1919)

‘Had there been no Miss Ivens, there would never have been a Royaumont’

When war broke out, Frances had initially planned to join the Women’s Unit in Belgium under Mrs Stobart but this unit had to withdraw in the face of the German advance. Undeterred, Frances volunteered for service with the newly formed Scottish Women’s Hospital (SWH) unit bound for France.

The SWH movement was founded in 1914 by the Scottish branch of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Society under Dr Elsie Inglis after she offered her services to the War Office but was turned down. In 1914, and despite the backing of the British Medical Association (BMA), the War Office refused to allow women doctors for Foreign Service on the grounds that current legislation would not allow it. As the war progressed, the War Office were finally obliged to use their services but on a temporary contractual basis and commissioned rank was not achieved until the Second World War.

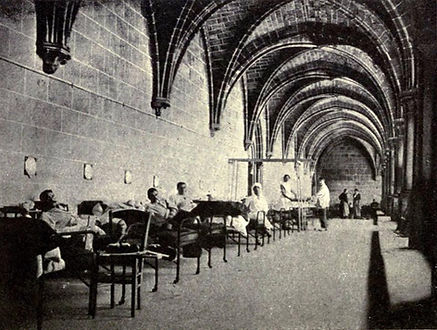

So, in December 1914, at the age of 44, Frances made her way to France as head of a unit of the Scottish Women’s Hospital (SWH) to set up a hospital, staffed entirely by women, at the Abbaye de Royaumont (about 30km north of Paris), to treat the French wounded from the Western Front. Prior to the First World War, Frances' practice had been confined to women and children only, she had never treated men, and she had absolutely no experience of treating battle casualties. Undeterred and determined to help in the war effort, she read widely on the subject, especially articles by Sir Robert Jones on fractures under war conditions. Her voracious reading on the subject is evidenced by the books she later donated to the Liverpool Medical Institution.

Initially at Royaumont there were no utilities such as electricity and water, nor were there any comforts, not even beds. But by sheer hard work, iron will and steady resolve, Frances and her fellow medics, orderlies, admins, drivers etc. gradually turned Royaumont in to a hospital.

Frances’ gifts of perseverance and diplomacy became invaluable when dealing with the French authorities. Operating under the banner of the French Red Cross did not obviate the need for permission from the French Military to treat French soldiers. The doctors had to prove their credentials by providing a copy of their Medical Registration, obtain the necessary military permits to collect the wounded from the clearing stations and get permission to drive vehicles in a war zone. They worked day and night to get the dilapidated building ready for inspection, but the Service de Santé deemed the layout and the facilities of the hospital unsuitable.

Image courtesy of www.avenuevertelondonparis.co.uk

Disappointed, Frances tried not to ‘take official snubs too much to heart’. Chauffeur Prance described how Frances ‘was admired perhaps most of all for her quiet courage and persistence in overcoming the understandable hesitation of the high French authorities ... and how with infinite patience Miss Ivens gave herself up to this wearying work.’

Antonio de Navarro was a visiting archaeologist (just what you need when you're trying to set up a hospital in a war!) writing a contemporary history of Royaumont Abbey. He captured the mood after the failed inspection: 'It was a night of discouragement and perplexity. Those of sensitive temperament surrendered to the conviction that the Service de Santé being antagonistic to the idea of accepting the services of women as doctors and surgeons had discovered in a physical objection a subtle means of refusing their proffered assistance. To those of a stronger fibre the threatened difficulties did but whet their appetite to face and overcome them triumphantly. Despite the terrible conditions Ivens went to task to adapt Royaumont Abbey into a hospital and she persevered after the first failed inspection.'

To restore staff morale, Frances organised Christmas festivities and this proved a turning point for the hospital. (Again in 1915, after a particularly gruelling allied offensive and a very demanding week, Frances bought champagne and gave the staff a ‘spanking supper’ and fancy dress party to celebrate the anniversary of the opening of Royaumont.

To save the SWH Committee of embarrassment in the face of this rejection, Frances tactfully brushed over the failed inspection. When the facilities were finally approved a few weeks later, she reported that ‘after inspection by the Service de Santé, the hospital opened on 13 January 1915, as Hôpital Auxiliaire 301, fully equipped for the reception of surgical cases.'

Initially, Royaumont was a 100 bed war hospital. By the end of the conflict this number had risen to 600. Operating under dreadful conditions, often under shellfire, by the light of candles but helped by orderlies, Frances worked until 2 or 3am but was then back on the wards by 7am to check on her patients.

Royaumont Abbey - in 1915 and as it is today

When naming the different wards, Frances ensured that they paid homage to all the parties involved: The founder of the SWH movement with the ‘Elsie Inglis ward’; France, their host country together with Mr Edward Goüin the owner of the Abbey, with the ‘Blanche de Castille ward’ (mother of the founder of the Abbey); and finally they acknowledged the generosity of a major benefactor from Ottawa with the ‘Canada ward’.

As the SWH was entirely funded through donations, Frances was conscious of the importance of public relations. She unashamedly used her feminine charms to impress the many visitors to the Abbey (among them Sarah Bernard, the Queen of Serbia, Raymond Poincaré and his wife and Maréchal Joffre;). Most importantly, she convinced the French Military authorities: ‘by persuasion of her powers of fascination she induced the commanding officers to send us cases and the 100 beds were soon filled and the hospital never again lacked work’.

Frances had considerable problem solving skills and a great sense of fairness. Dr Louisa Martindale, who visited Royaumont, remarked: ‘Most of all I was lost in admiration of the splendid organising and administrative powers of the CMO (Chief Medical Officer), Miss Ivens – of her endurance, courage and above all her surgical skill.

She was an experienced administrator who adroitly juggled the demands of the Committee of the SWH in the face of the dire financial needs of the hospital. Refusing a pay rise for herself and even donating her own wages, Frances successfully lobbied the SWH committee on behalf of her nurses, orderlies and chauffeurs for better working conditions, better food and increased pay and status. She valued and developed staff at all levels but was particularly appreciative of the work of the orderlies whom she considered the backbone of the hospital.

Dr Frances Ivens surrounded by orderlies outside Royaumont Abbey.

Royaumont Archives

Frances was sometimes guilty of being dismissive of qualified nurses and clearly felt more at ease with orderlies who she thought ‘did more work and with more intelligence than an inferior type of fully trained nurse’. She suggested that orderlies should be promoted to the status of ‘auxiliary nurse’ with the idea that gradually they could replace some of the sisters. This understandably caused friction with the nurses who had gone through three years of training to qualify but also often came from less privileged backgrounds and enjoyed less financial security than the orderlies.

At the beginning of the war there was an element of uncertainty with regard to women being allowed to drive, so two men were employed as chauffeur-mechanics at Royaumont. However, once the women chauffeurs had proved their proficiency, Frances wanted the men gone. She successfully wrote to the Committee, playing the patriotic card: 'It places me in a very awkward position to have useless men hanging about when we have any of the French authorities here if they are of military age, for there is a distinct feeling that England is not doing its utmost and it is most humiliating – not only that but it does not look well to pose as a woman’s hospital and yet have men here... it exposes us to criticism.'

Dr Frances Ivens with some of the Senegalese patients in the grounds

of the Abbey. Mrs Hayward photo album, Royaumont Archives.

During the Somme Offensive, Royaumont faced a large influx of colonial troops in particular Senegalese and Arab patients who didn’t always see eye to eye. Apart from creating segregated wards (unthinkable today), Frances dealt with instances of racism among patients and from staff with tact, sensitivity and leadership. She didn’t hesitate to dismiss an orderly who wrote to complain: ‘It is also most unfitting that white women should attend to natives in the ways we orderlies have to, as it will tend to lower the prestige of the white women in the East, as anyone who has lived in India well knows.’

She would continue as Médecin Chef until February, 1919, with only one period of leave in England, which she spent largely in lecturing to raise money for the hospital.

Between 1914 and 1919, Frances, her second in command Dr Ruth Nicholson and their team treated over 10,861 patients including 8,752 soldiers. The bulk of the major surgery was carried out by Frances and Ruth. The remarkably low mortality rate of 159 or 1.82% was lower than similar military hospitals. No doubt a large contributor to this fact is the Royaumont doctor's pioneering new approach to the treatment of gas gangrene, using X-rays and bacteriology for diagnosis, followed by extensive surgical debridement of the affected tissue. Francis published accounts of these in the medical literature of the day and Lydia Henry, also a doctor at Royaumont, postulated that it was this cooperation of different branches of the profession which allowed them to fight infection and avoid unnecessary amputations. They were also able to use antiserum supplied by Professor Weinberg, an eminent bacteriologist at the Pasteur Institute in Paris. The hospital was inspected and approved by many French generals and government officials, and its reputation was largely due to the leadership of Frances Ivens.

During the Battle of the Somme, when the number of beds increased to 600, the surgeons and doctors (typically four of them at any one time) worked for eight days with only sixteen hours of sleep.

Leading by example and putting the patients and the hospital first, Frances obtained outstanding commitment from her staff. Roslyn Rutherford, an Australian masseuse described a busy period: 'The three theatres are going night and day without ceasing and also the two X-ray rooms. The poor Chief looks dreadful, but never gives in and never allows a big op to be done by anyone else. She is a top-hole surgeon, but has cured me of all desires in that direction.' Rutherford later also commented: ‘The hospital is a perfect purgatory but, notwithstanding which, we are contemplating signing on again for another three months. We both feel that they give us so much, it is rather dirty to leave at the end of six months, if the war is still going on.’

Miss Frances Ivens (seated) with some of her staff. From left to right:

Miss Ruth Nicholson Surgeon and 2nd in command; Dr Marie Manoel Bacteriaologist; Dr Elizabeth Courtauld Physician and Anaethetist; Dr Leila Henry Assistant Surgeon and youngest doctor

Frances’ human understanding towards her patients, who affectionately referred to her as ‘Madame la Colonelle’, permeated the entire organisation. In 1919, at the first reunion of the Royaumont and Villers Cotterêts Association, V.C.C. Collum, a radiology technician at Royaumont and one of the founders of the Association, gave a speech in honour of Frances Ivens in which she explained: 'She was ready to work us to death for it (the hospital). And when the call came we quite contentedly fell in with her views and just let her! Why was it? Because we all knew our Chief never asked any of her staff to do anything or face anything that she would not do, endure or face herself. She had a genius for scrounging talent and holding on to it.

Frances insisted on being woken to receive the wounded whatever time of day or night. When beds were in short supply she selflessly surrendered her own. She would often get up in the middle of the night to bestow a medal on a dying soldier.

Described by a newly arrived orderly as ‘a funny old bird’, Frances knew how to assert her authority. In her history of the SWH, McLaren described how the blessés (wounded soldiers) did a revealing skit on the advanced hospital at Villers Cotterêts: ‘The most amusing parts of the piece were the absolute calm and indifference on the part of the Staff at the explosion of a supposed bomb close by and the wild panic which takes place on news coming through that ‘La Colonelle’ (Miss Ivens) was on her way from Royaumont to pay the Hospital a flying visit!’

During what Eileen Crofton described as ‘their finest hour’ in 1918, a new orderly wrote to the SWH committee to complain about the lack of hygiene and the poor running of the hospital. Clearly with such an influx of wounded, the women were under enormous pressure and Frances wrote a defensive and unashamedly political reply putting an end to all argument: ‘The Sous- Secrétaire d’Etat du Service de Santé sent for me on Sunday to see him at the Ministère de la Guerre, when he said that he regretted very much that all hospitals were not modelled on Royaumont, as he considered it quite the best going.’ Some accused her of lacking a sense of humour but her answer to the SWH committee’s complaints about the cook Michelet refutes this: ‘If you had been here from the beginning, you would know that the cooks had always quarrelled with other cooks. Michelet has his faults but he cooks meat splendidly’.

In 1917, at the request of the French Military authorities, another advanced tented hospital was established at Villers Cotterêts, much closer to the front lines. There, Frances operated under shell fire during the 1918 German advance until they were forced to evacuate back to Royaumont. When at last the armistice was signed on 11 November 1918, much rejoicing took place at Royaumont and Frances was ‘chaired’ by the orderlies around the place and she gave all the staff a day off to go to Paris and join in with the celebrations.

Another quote from V.C.C Collum sums things up beautifully: 'had there not been an Elsie Inglis, then there would not have been a Scottish Women’s Hospital. So had there been no Frances Ivens, there would have been no Royaumont Abbaye, we just held up her hands.'

After nearly five years of intense involvement, the transition to peacetime work must have been difficult for these women. Many ‘old Royaumontites’, as they called themselves, described their time at Royaumont as the most rewarding of their lives. Frances was bitterly disappointed at the end of the war when her plans to run a canteen for the occupying army at Mayence were turned down by the SWH committee: ‘it is distinctly depressing to us to feel that the work that we have done for the French is to be allowed to drop completely’.

In recognition of her service at Royaumont she was decorated by the French President with the Cross of the Légion d'honneur. In December 1918 she received the Croix de Guerre with palm, the citation reading: "...having ensured, day and night, the treatment of French and Allied wounded during repeated bombardment at Villers Cotterets in May 1918. On the approach of the enemy she withdrew her unit at the last moment to the Abbaye de Royaumont where she continued her humane mission with the most absolute devotion”. She was also awarded the Médaille d'honneur des épidémies. In 1926 she was awarded the honorary degree of Master of Surgery ChM and was also awarded a CBE thus becoming a Commander of the British Empire.

Post War

At the end of the war Frances returned to hospital practice at the Stanley and the Samaritan hospitals in Liverpool. She was closely involved with the rebuilding of the Maternity Hospital, and with the formation of the Liverpool Women's Radium League. She was also a leader in the establishment of the Crofton Recovery Hospital for Women. In 1925, Frances was awarded an honorary Masters’ degree by the University of Liverpool. In 1926, she became the first woman to be elected Vice President of the Liverpool Medical Institution, one of the oldest medical societies in the country. Following her appointment as a lecturer in Obstetrics and Gynaecology at the University of Liverpool, she was awarded an honorary degree of Master of Surgery (ChM) in 1929 and also became a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in recognition of her public service. That same year, she became founder Fellow of the Royal College of Obstetricians, She was elected president of the Medical Women's Federation from 1924 to 1926 and during her tenure she actively promoted the role of the 1000 medical women she represented. Her conviction was that ‘medical women should take their share in the great schemes of reconstruction and re-organisation’. She also continued to lecture to students, encouraging them to ‘devote themselves to medical research to assist in the advancement of medical knowledge’. She raised a variety of issues; the status of women doctors, equal remuneration for women doctors, the Married Women Employment Act and the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Bill, the admission of women to medical school and co-educational medical education.

Frances was particularly vehement with regard to the availability of training posts in hospitals. In 1925, she criticised those few medical schools which still admitted women but denied them access to resident hospital appointments: ‘Whilst giving equal opportunity to men and women as far as graduation, they do not realize their further responsibilities and they have made no effort to throw open to their women graduates the resident posts in their own hospitals.’

One of her main campaigns was for the improvement of health provision for women and children. Having first raised the issue of birth control in 1921, she was still campaigning on the subject in 1933 when she gave a talk to the South West Essex division of the Metropolitan Counties Branch of the BMA entitled, ‘The scope of birth control in preventative medicine’.

In her capacity as Chairman of the Midwives Committee of the Medical Women’s Federation, Frances was involved in political issues until 1930, discussing the remuneration of practitioners attending complicated maternity cases.

In 1930, at the age of sixty, she married an old friend from her student days, Charles Matthew Knowles, a London Barrister and leading expert on Railway Law in Britain. They married in Liverpool Cathedral in front of family, friends and many of Frances' ex-staff and patients. Fifteen of her old Royaumont colleagues formed a guard of honour and shouted “VIVA LA COLONELLE” a cry often heard from the wounded French at Royaumont during the war.

Soon after the wedding Frances and Charles moved to Kensington where Frances continued as a consultant. When Charles, (who had previously been widowed in c.1918 and had a son from his first marriage), decided to retire they moved back to the original Knowles family home, Killagordon, in Truro, Cornwall. It was here that Frances really relaxed for the first time and became an award winning gardener. The rose garden at Killagorden was a a place that many people visited over the next few years.

She was succeeded in her posts in Liverpool by Ruth Nicholson, her assistant from Royaumont.

Frances would continue to travel to France in the inter-war years and would visit former patients and many of the wounded whom she had treated at Royaumont wrote regularly to her. She also kept in touch with former staff members who would meet annually at the annual dinner of the Royaumont Association.

Frances continued her association with fellow Royaumontites, not only as president of the Royaumont and Villers Cotterêts Association but through her friendships with many of the doctors. In 1928, she attended the International Conference of Medical Women in Bologna, journeying there by car with Louisa Martindale. That same year, after a holiday spent in France with radiologist Dr Agnes Savill, they visited Royaumont on their return only to find that l’Abbé Rousselle, the local vicar who had been such a solace to them during the war, had died that very day.

Frances maintained her interest in medical research and published her clinical findings in a book entitled ‘Caesarean Section’ in 1931.

Second World War & Death

On the outbreak of the Second World War Frances acted as Medical Officer of Health for Cornwall (Red Cross) and was also Chairman of the Cornwall committee of the Friends of the Fighting French.

On 6th February 1944, Frances spoke to her housekeeper about the day’s business and walked through to her breakfast room, where minutes later she was found on the floor in a coma to which she would never wake up. She had suffered a Cerebral Bleed which proved fatal and she passed away later at Truro City Hospital. Her funeral was held at nearby Kenwyn Church attended by several colleagues from her Royaumont and Liverpool days. Her friend Dr Laila Henry wrote; "Frances was buried in a beautiful spot beneath a beautiful Copper beech tree."

The Search For Her Grave

After looking for Frances' elusive grave for a number of years, Sue finally found it in July 2021, indeed, beneath a large copper beech. It was neglected and sadly abandoned; overgrown and the kerbs rotting away with age. On the bottom kerb it still faintly says Frances Ivens-Knowles 1870-1944. Permission has been sought and given by the church and after an extensive search for relatives, we at Wenches in Trenches have raised the funds to have the grave of this wonderful woman refurbished and hope to have a ceremony sometime Spring 2025 All will be welcome.

Our thanks to the following for their diligent research and archival material:

- Sue Robinson

- Marie-France Weiner - https://web.archive.org/web/20180223051018/http://www.evolve360.co.uk/Data/10/PageLMHS/Bulletin26/weiner.pdf

- The British Medical Journal

- Royaumont Archives

- Eileen Crofton - author of The Women of Royaumont